Hanging with Habeck

We just don’t know, do we? We live our lives planning for the next great unknown, never seeing the asteroids. Sharp reminders of our mortality, dinosaurs have intrigued humans since we first unearthed their bones.

Like many of us, Louis Habeck’s fascination with dinosaurs began when he was a kid. There’s something about the enormity of these creatures, their global dominance, and their sudden extinction that captivates childhood imaginations.

“There is so much that we can’t study. Instead, we imagine what they were,” Habeck said.

Habeck, a Billings-born artist, always wanted a life-sized dinosaur mount on his wall, though he lacked the space to create and hang one. Partial to the triceratops, Habeck envisioned creating a to-scale head and using the giant bony frill that juts from its forehead as a canvas on which to paint.

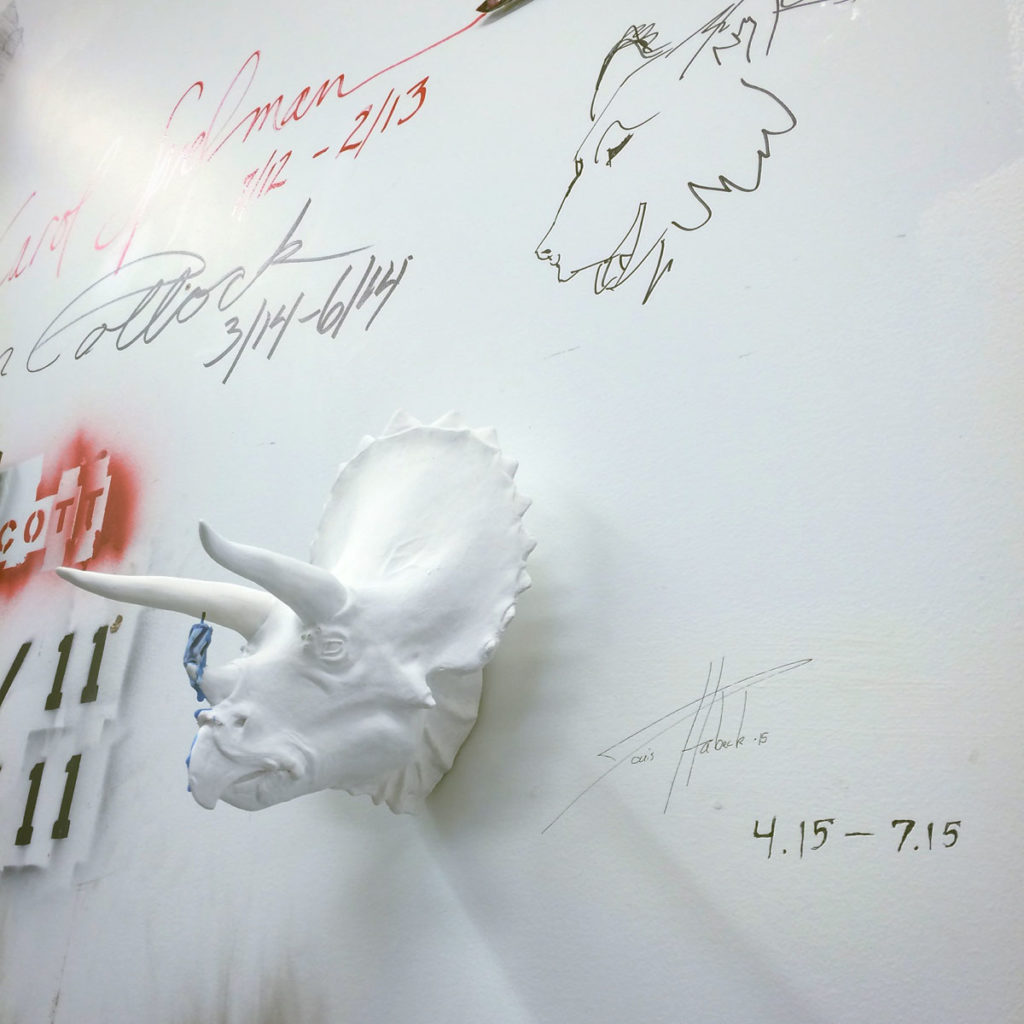

Creating a life-sized triceratops head became a reality when he was asked to be Yellowstone Art Museum’s ninth artist in residence from April – July 2015.

Liz Harding, Yellowstone Art Museum Associate Curator, described the residency as a path to becoming more established at the museum and in the artistic community. “It’s a good launching pad,” she said.

Looking at the scope of Habeck’s talent, he doesn’t need a launching pad. He’s already working on the moon. During his time at the YAM, Habeck settled into the studio, hanging mounts of imagined animals he’s created on the walls. On display were casted creatures, from bird fetuses to a donut-shaped character with a bite taken out of him to wearable masks that could be used by Muppets guesting on Where The Wild Things Are.

Meet the Creator

Habeck, born in Billings and raised on an acre and a half of land in the Heights, grew up surrounded by family pets and livestock. Habeck’s parents provided him a plethora of children’s books filled with colorful illustrations and creative, sometimes dark creatures.

“I don’t think I ever really read them,” Habeck said. “I’d just go through and look at the images. I still do. That really motivated me and informed my work.”

Habeck’s work spans many mediums. He draws, often informed by old photographs he’s collected. Others portray imagined creatures or personified animals in human attire. He paints with watercolors, dressing up his drawings in soft pastels. He sculpts real and imagined creatures, creates prints using intaglio techniques, runs a photography business taking unique portraits, and shoots events for Lilac restaurant.

Habeck’s line of business animals began as a birthday card and evolved into a series of drawings exploring the various personalities of animals through expression and attire.

“What would a moose do if he could be a human? Would he enjoy going to work?” Habeck asked. “I could be doing portraits of humans, but that’s less interesting to me. These animals are relatable and compassionate. You can feel emotions for them and treat them as if they were real.”

In his Subboreal Studios, Habeck runs what he’s dubbed the Imaginarium. This is where his three-dimensional creations come to life. These whimsical creatures are dark, yet playful, with a worried look to them.

“They might look creepy and intimidating, but they are not malicious. They are misunderstood,” said Habeck. “They have something that looks like it could be real and you believe—even though you’ve never see it before—that it could have been alive.”

Just as a person has distinctive facial features, Habeck’s creations have a relatable, sometimes worried look. They personify glum in an approachable way, their past life and struggles on display through the upturn of their eyes and the downward angle of their mouths.

“Through the eyes and a creature’s gesture and posture, I am not saying everything about them, but allowing people to look into their personality,” Habeck said. “They didn’t just become a piece on the wall without a story, a little scar, a missing tooth.”

Suspension of Disbelief

When the YAM residency was offered to him, Habeck finally had the space he needed to create a life-sized triceratops head—the largest piece he’s ever constructed. “I wanted that feeling of something massive, something that is bigger than us,” he said.

To prepare, Habeck studied drawings from fossilized records and photos of triceratops skin impressions. He read extensively on detailed bone structure and measurements of the skull. Part of his challenge to himself was to make it feel real.

“You take this bone artifact and cover it with imagination. There is a lot of flesh and muscle we can’t study,” Habeck said. “I tried to get as accurate as possible, but at a certain point, you have to take creative control.”

“You take this bone artifact and cover it with imagination. There is a lot of flesh and muscle we can’t study.”

This triceratops head began with sheets of pink foam board glued together to form a square. Habeck began whittling away, creating a series of gentle curves to shape the skull, imagining what muscles would be there, knowing he would add clay later.

After the foam base took shape, Habeck skinned the surface with a half-inch of oil clay, which never dries or hardens. Adding shape with clay made the form incredibly realistic, and Habeck began to tell a story with the skin details.

Avenue of Function

Building a triceratops to actual size involves a lot of simulated skin and imagined life. The push and pull of flesh over the form, the blood vessels coursing though the frill, and the varying sizes of scales and scars gives the sculpture life and a sense that it existed. In recreating and inventing scars, dimples, a smile or a frown, Habeck began to tell a story of how this dinosaur moved and lived.

“They were living and thriving and evolved for millions of years. This isn’t a dragon that someone made up,” Habeck said.

Habeck was able to view a mummified dinosaur in Bismarck, which inspired him to shape the clay with a softer, more wrinkled skin. Dinosaurs in the past have been represented as very reptilian with hard skin, yet it’s theorized that dinosaurs were more birdlike than reptile.

“You could see the layers of skin. It was incredible,” Habeck said. “I knew I wanted that esthetic.” He began implementing skin scales, obtuse hexagonal and pentagram shapes he created by stamping the clay with the end of a brass pipe, varying them in size based on the proximity on the dinosaur.

“When I started putting scales on it, I didn’t initially like the way it looked,” Habeck said. “It was a smooth form for so long, but as I added more and more, figuring out where they should be, what sizes, the mechanics of it, it started looking better. Now it’s just a matter of completing the scales.”

Habeck anticipates the final scale count will exceed 20,000.

Moving Spaces

Once the clay (more than 100 lbs of it) exterior has been carved to satisfaction, Habeck will make a silicone rubber mold of the sculpture. The process is a bit meticulous to ensure a clean mold.

Removing the silicone rubber will destroy the clay’s detail, but Habeck can recycle the clay. “If you rush the mold and have a bad cast, you are wasting hundreds of dollars.”

The final steps are to inject expanding lightweight foam into the mold to create a hollow cast. The finished cast can be painted and reproduced as many times as Habeck needs.

Though he wanted to start molding the project before leaving the YAM, Louis is content with the progress made. He moved the triceratops out of the YAM open studio into his home studio to continue working on the clay and scale details.

“I had no idea how long this would take, having never done anything of this scale and complexity,” Habeck said. “Sometimes you can’t work on something every day. I wish I had more time, but it is enjoyable to step back after working on it all day and saying, ‘It’s looking good.’”

Every step of the process, the life force of this creation seemed larger. Its presence, the grand scale of presentation struck me every time I visited Habeck. I could see the skull underneath, the saggy flesh of the neck from years of movement, the vessels popping from the frill, coursing blood into this growing bone structure.

Of his creations, Habeck said, “To empathize with them, to believe they are real—that is a big compliment to me. To treat them with a human-like compassion…If I have been successful, that is how I measure it.”

Habeck will debut his finished work at the Northwest Gallery in Powell in January, and a show date at the YAM TBA.

More info: Habeck.daportfolio.com

DID YOU KNOW?

- Triceratops have the largest skull of any land animal in the history of the planet. A life-sized triceratops skull can reach more than eight feet across.

- Created from foam and covered in clay, Habeck’s creation measures 6 feet tall, 4 feet wide and weighs just under 140 pounds. When cast it will weigh an estimated 30 – 40 pounds.

- An actual Triceratops head is estimated to have weighed 1,000 pounds–10 times as much as a moose or bison head.

- It’s been suggested that dinosaurs developed a birdlike characteristics: they were less like mammals with horns and skulls built for colliding and fighting each other and more like birds with decorative frills. The triceratops frill was a type of bone ornament for display that could be used for defense, but was not developed solely for such purpose.

- A triceratops frill took upwards of 30 years to grow, and it grew faster when conditions were favorable, though not constantly. Triceratops went through tremendous growth periods; in a couple years they were as big as an elephant.

- The frill was a living piece of the dinosaur, and the supraorbital horns and frill were constantly growing, creating a balancing act to help leverage and wield such horns while supporting the neck. Jaw strength was also tied to the frill. With a sharp beak for eating woody vegetation, the triceratops had huge muscles to chew such roughage.

- Once the sculpture is finished, it will be molded so copies can be cast and painted. If cast in solid milk chocolate, it would contain 2.7 million calories. At a caloric consumption of 2,000 calories today, it would take 3.7 years to eat it.

- More than 700 hours so far have been spent researching and sculpting this piece, which includes carving and shaping of roughly 7,000 individual scales across approximately 35% of the head’s skin surface, with an anticipated final count 20,000 scales.

This article originally appeared in Noise & Color’s final issue, published September 2015. Cover image and progress photos by Louis Habeck.